Opinion Editorials state the views solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Community Journal.

By Brad Wilson

In his recent guest column, Sam Byrne, managing partner of CrossHarbor Capital Partners, offered an apology to the Shields Valley community for missteps in water use at Crazy Mountain Ranch and reaffirmed a commitment to stewardship and long-term investment. That acknowledgment is welcome. But it’s only the beginning of the conversation Montanans deserve.

When the South Crazy Mountain Land Exchange was first proposed in Fall 2019, the 18,000-acre Crazy Mountain Ranch (CMR), known locally as the Marlboro Ranch, was still owned by Philip Morris USA, operating under its parent company Altria Group. The Forest Service’s proposal included a component that would have transferred portions of CMR into public ownership—most notably Rock Lake, which is at the center of the ongoing water saga controversy.

In early 2020, Friends of the Crazy Mountains and its partners met with Tom Glass, a representative of the Yellowstone Club, to discuss the East Crazy Inspiration Divide Land Exchange—a proposal Glass had helped develop. During that meeting, Glass assured the group that the Yellowstone Club, also owned by CrossHarbor Capital Partners, had no further interest in the Crazy Mountains. The club’s involvement, he explained, was limited to advancing the proposal so it could acquire 500 acres of Forest Service land in the Madison Range, adjacent to its existing holdings.

In late 2020, the U.S. Forest Service deferred the CMR component of the South Crazy Mountain Land Exchange, citing public opposition. Conservationists, hunters, and tribal representatives had raised valid concerns: the proposed swap threatened public access, fragmented wildlife corridors, and lacked transparency. On the surface, it looked like a win for public input.

But then came the twist.

Just months later, in June 2021, CrossHarbor Capital Partners—known for transforming Montana’s wild landscapes into luxury enclaves—acquired the 18,000-acre CMR property. The timing was uncanny. The deferral removed the ranch from a complex public exchange, and soon after, it was in private hands, poised for development.

This sequence of events raises a troubling question: Was the deferral truly about listening to the public—or was it about clearing the runway for a high-dollar acquisition?

CrossHarbor’s footprint in Montana is well established. From the Yellowstone Club to Moonlight Basin, the firm has reshaped vast swaths of land into exclusive retreats. Its purchase of CMR fits the pattern. But what’s less clear is whether the Forest Service’s decision to defer the exchange was influenced—directly or indirectly—by CrossHarbor’s interest in the property.

If so, it would mark yet another instance where public land decisions are shaped not by democratic process, but by private ambition.

Montanans deserve transparency. They deserve to know whether their voices genuinely influenced the deferral—or whether those voices were a convenient cover for a deal already in motion. The Forest Service owes the public a full account of its decision-making process. And CrossHarbor, if it values its reputation in this state, should be forthright about its role in the timing of the acquisition.

Public lands are not bargaining chips. They are the shared inheritance of all Montanans—ranchers, hikers, hunters, and tribal nations alike. When decisions about those lands are made behind closed doors, trust erodes.

Montanans are not anti-development. They are pro-transparency, pro-access, and deeply protective of the landscapes that define their way of life. Stewardship is not just about investing capital or creating amenities. It’s about earning trust through openness, accountability, and a willingness to engage with the community; not just informing it after decisions are made.

Crazy Mountain Ranch still has the potential to be a model for responsible private ownership in a region where public and private interests often collide. But that will require more than apologies and assurances. It will require action, humility, and a genuine partnership with the people who call Shields Valley home.

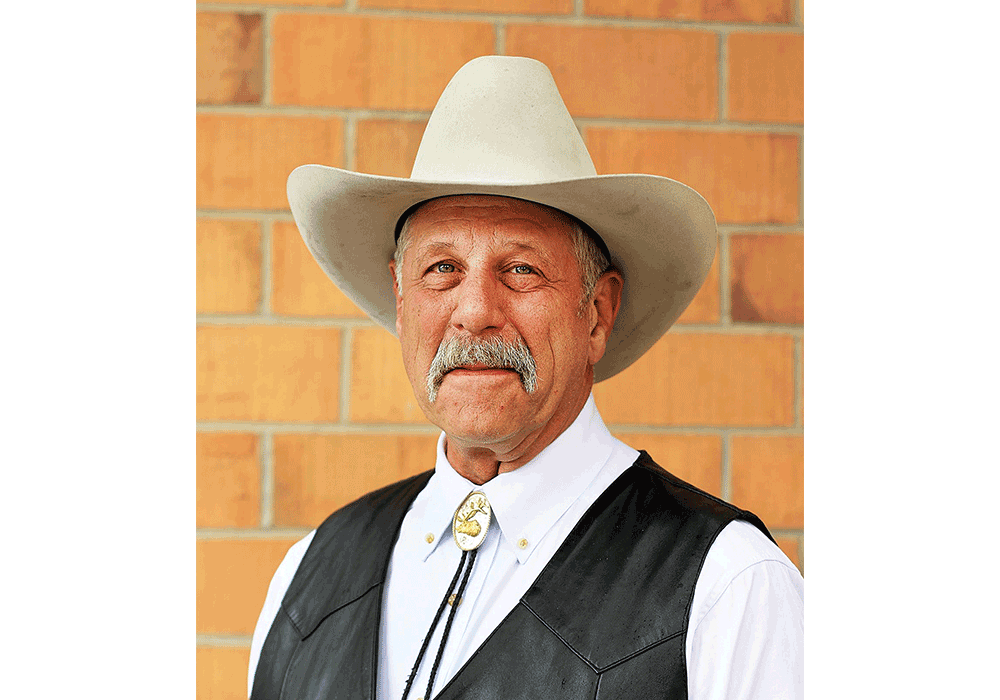

Brad Wilson, of Wilsall, is founder of Friends of the Crazy Mountains. His family has over 100 years of historic use on public lands and the public trail systems in the Crazy Mountains.