Big Timber—An estimated 70 residents attended the public hearing and regular city council meeting scheduled for Monday, August 4th located at the Carnegie Library on 314 McLeod Street in Big Timber. The meeting, led by Mayor Greg DeBoer, primarily concerned resolution #1044, an amendment to the city’s budget for fiscal year 2024 – 2025. However, the proverbial elephant in the room sat quietly in anticipation, noted by Mayor DeBoer as he quipped, “It’s like you guys are waiting for something,” shortly after proceedings commenced.

Reports have surfaced that the City of Big Timber is now selling an average of 100 thousand gallons of water daily (initially reported at 27,000 gallons, though since clarified by Big Timber Public Works Director Kris Novotny) to the infamous Crazy Mountain Ranch (CMR) amidst a controversial water rights dispute in the Shields Valley, recently settled through a lawsuit filed by the Department of Natural Resource Conservation (DNRC) upon receiving a flurry of complaints from neighboring ranchers claiming misuse.

CMR had, for nearly two years, appropriated water resources in order to irrigate an 18-hole private golf course currently under construction, eventually discontinuing irrigation just one day prior to the DNRC filing the lawsuit which alleged illegal water use—initially refusing to comply with a preceding cease-and-desist order.

In the weeks leading up to the lawsuit, CMR approached Big Timber Municipal about regularly purchasing bulk water supplies to compensate for this loss, an arrangement facilitated by Bullock Contracting LLC, a general contracting company based in Big Timber. Owner-operator Buster Bullock and his crew employ a small squadron of tankers to transport treated water to CMR each day—extracted from the nearby Boulder River.

The arrangement between Big Timber municipal and CMR, documented in part by the Montana Free Press Association since mid-July, has allegedly unfolded over several weeks, amounting to a barrage of complaints from locals denouncing it as patently immoral in light of water rights violations committed by the now notorious organization, as well as increases to commercial and residential water rates (historically inexpensive yet recently and necessarily adjusted to account for inflation).

Following monthly reports from the Sheriff’s and Public Works department, public commentary at the meeting began with opening statements by DeBoer, who would persistently reiterate on several occasions that the city, well within it’s rights as a municipality (a notion later questioned during public commentary and confirmed by City Attorney Jim Lippert with consultation from DNRC counsel), had sold bulk water to various entities both private and public for at least 30 years—a decision he vehemently upheld, citing examples of other large-quantity transactions negotiated by the city yet without reproach from residents.

He further clarified that bulk water sales place no undue strain on the city’s water supply or system, and that any indication otherwise would warrant suspending such transactions. According to the Mayor, the agreement with CMR is non-contractual and on a limited basis.

Councilman Justin Ferguson indicated that the all-inclusive costs (including water system employee wages and loan payments, amongst other expenses) to process bulk water sold at $14 per one thousand gallons is roughly $6. In other words, the city profits virtually $8 per one thousand gallons sold in bulk, totaling nearly $800 daily (a whopping $24,000 monthly) as a result of its current arrangement with CMR.

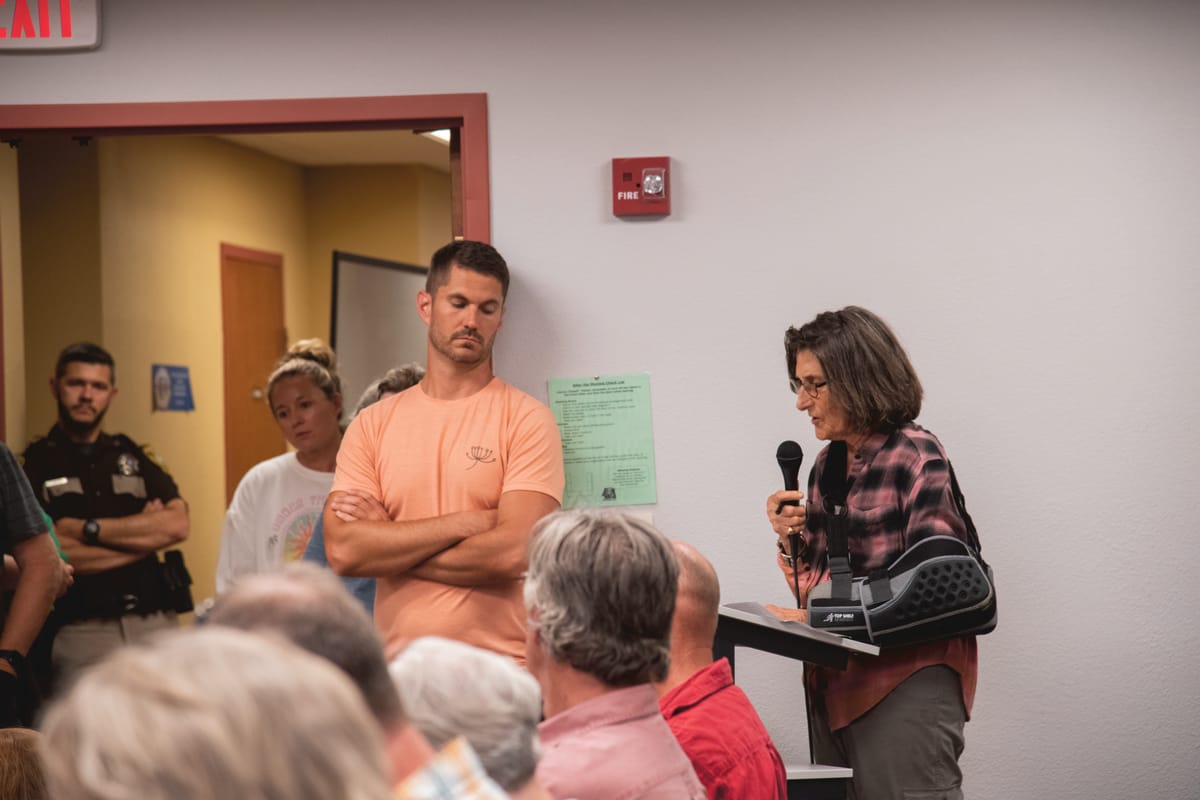

Several residents then took to the podium to express indignation and demand answers for questions regarding the legal ramifications and financial implications of this decision—specifically how bulk water sales rates are determined and whether profits are being used to benefit the community. Many speakers suggested raising rates or adding surcharges to offset controversial increases to water costs and repair city roadways.

DeBoer explained that profits procured through bulk water sales are stored in coffers reserved for ongoing maintenance of the city’s water system, including replacing aging water lines and repairing facilities and equipment in accordance with a set budget. He clarified that progressively rising usage rates (now approximately equivalent to the state median) are independent from bulk water sales and that profits may not be used for purposes other than to support existing water system infrastructure if and when necessary—aged and aging, increasingly costly and unpredictable, requiring both major investments and precautionary funding.

To this point, commissioner Leonard Woehler explained that repairing damaged water and sewage lines indirectly benefited city roadways and that such projects had been ongoing contingent upon funding—otherwise obtained by increasing usage rates for citizens, a decision recently deferred by the council, per DeBoer.

According to DeBoer, water rates in the city of Big Timber were exponentially low with few if any incremental increases over the years to compensate for wearing infrastructure. Though recent progress has been made, the city is continuously seeking funding for long overdue repairs and other measures to expand and improve its water and sewage systems.

“This is a great opportunity to bring in additional funds for [improving] infrastructure without raising [usage] rates,” said Woehler, who attended the meeting virtually.

The bulk rate, according to notetaker Hope Mosness, was established in 2008 and, at that time, increased from $10 to $14. Increasing the rate arbitrarily, according to DeBoer, is not an option—instead, he discussed drafting a new bulk water sales policy, the need for which is unprecedented after 30 years.

He stated, “We want to make sure we have a sustainable, valid policy grounded in facts and reason,” stressing that indiscriminately increasing rates without developing and implementing a new policy may constitute discrimination, resulting in a potential lawsuit. “We’re not subsidizing wealthy people,” said DeBoer, who assured attendees that public input would be considered during this process, though without interjecting moral judgment into the finished product.

Other recommendations expressed during public commentary regarding the policy included but are not limited to annual incremental rate adjustments and rate differentiation for private/public sector and local/non-local entities—the latter of which would inherently affect sales to organizations like CMR, a private corporation located in Park County.

DeBoer stated that the council has begun this process and will continue addressing this issue in the coming weeks. A public hearing will eventually be held to adopt this policy by the council.

Comments furthermore addressed the potential environmental consequences and other ethical considerations of selling bulk water—for example, monitoring water levels of the Boulder River and maintaining a sufficient supply for potential fires and necessary irrigation in light of seasonal restrictions. Novotny insisted that these fears were unfounded, as water levels were assessed regularly to ensure bulk sales did not interfere with the city’s water capacity.

Questions also emerged surrounding speculation that CMR had inquired about purchasing bulk water from White Sulphur Springs, offering twice as much money but rejected, raising concerns about the city of Big Timber’s values.

Comparing this arrangement and other large-scale transactions conducted with businesses like JKL LLC, one resident said, “CMR is not doing us any good. They provide no public services.”

Consistently, the most glaring criticisms concerned the city supporting CMR in their mission—an exclusive club whose management knowingly and intentionally abused water privileges.

“This is a county of ranchers. We know what it’s like to support and honor water rights,” said another resident.